Preventative healthcare: designing for the service loop

A set of provocations about the design of digitally enabled preventative healthcare

There are some public services that are transactional in nature. Applying for a passport can, for most intents and purposes, be considered in isolation. You do it once and hopefully don't have to worry about it again for a decade.

With other public services, especially in areas like healthcare, welfare, social work or education, there is no single outcome, no single 'user journey'. There is an ongoing relationship between citizen, public services and public servants. These relationships are increasingly mediated by digital and are data-driven. The UK's Universal Credit, for example, is not just a welfare system, but one mediated through a digital account, and relying on a wide range of data sources. I've written previously about how transactional, utilitarian approaches to design don't really work in these contexts and how it requires a different approach.

To try and bring some of that approach to life, the examples in this blogpost are about healthcare, specifically, preventative healthcare.

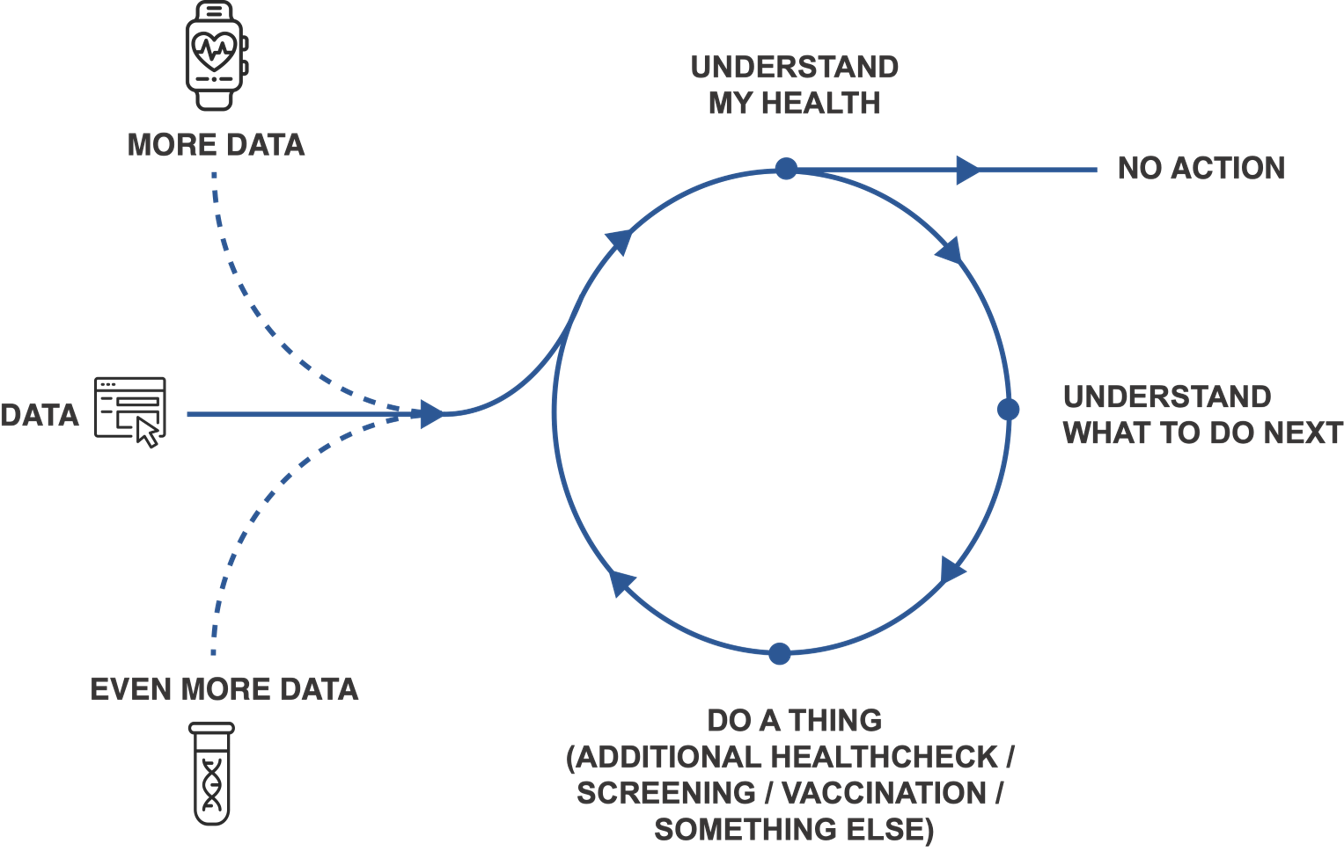

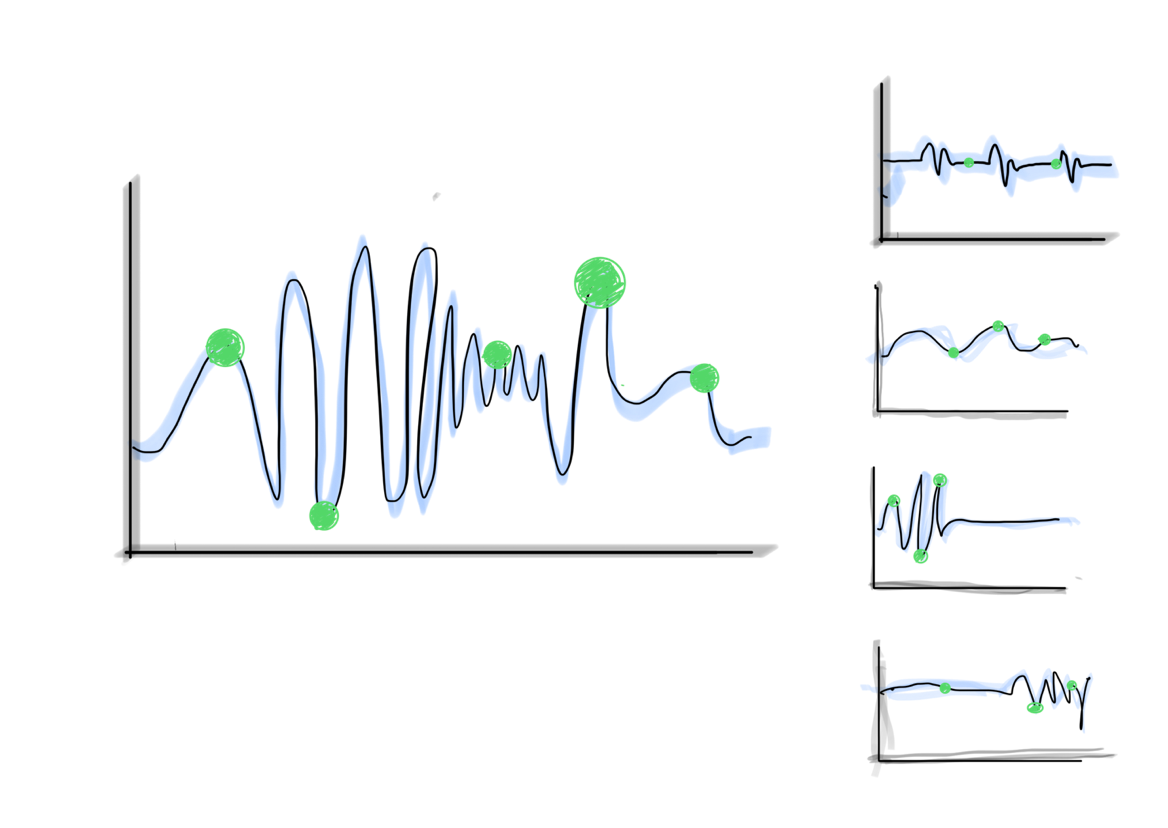

The service loop

We can think of digitally enabled services for preventative healthcare as a 'service loop' that looks like this:

- More data: it seems like a safe bet that advances in wearable technology, interoperability, diagnostics and AI mean that, over time, there will be more data about our health

- Understand what it means: users and clinicians, need to be able to understand that data

- Understand what to do next: they need to understand what they can do next (or decide to do nothing)

- Do a thing: then they need to complete the thing they have chosen

- More data (again): every action, for example, completing a smoking cessation programme generates more data

This framing is useful because it can help us think about the types of interactions digital-first healthcare products, like the UK's NHS app, need to support each time someone passes around that loop, and how to couple together some very divergent service journeys into something coherent.

Please note: what follows is a series of provocations, rather than definitive answers. I hope it spurs similar provocations from others.

More data - an irrigation system, not a firehose

It doesn't take a futurist to predict that in the near future there will be more and more data about our health. Rather than thinking about this as a firehose of information, those designing digital healthcare systems will need to exercise discretion and be clear about intent.

Instead of aiming to pipe more data into the hopper, digital teams will need to be clear about the data types that really matter and focus transformation effort on those. This is what India's Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission did with the Unified Health Interface, starting with common well-known things like vaccination records, discharge summaries and wellness records.

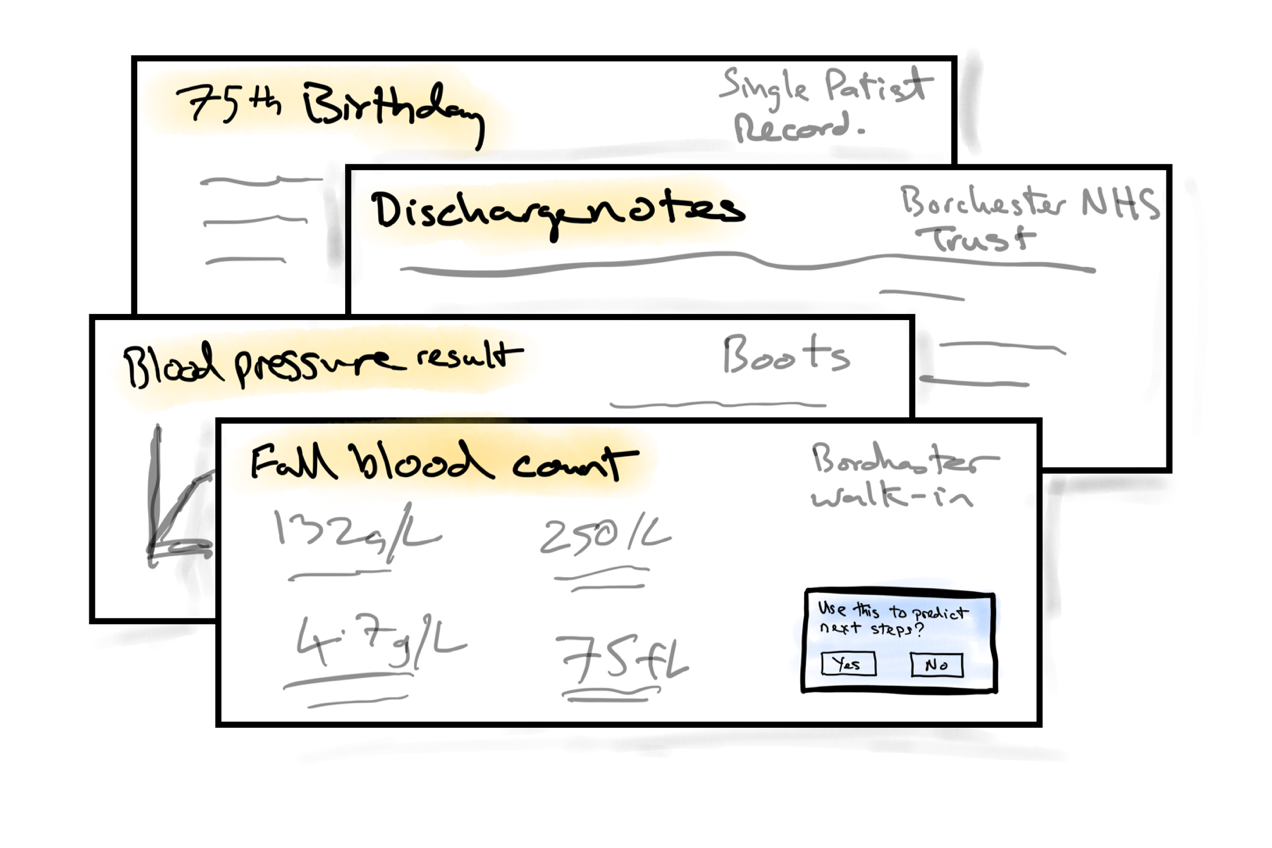

That is partly about impact, but also about grounding data-driven services in things that are tangible - a birthday, a discharge note or a test result.

When data comes from third-parties - for example wearables or social prescribers - that will likely benefit from grounding in the clinical intent behind the data being collected.

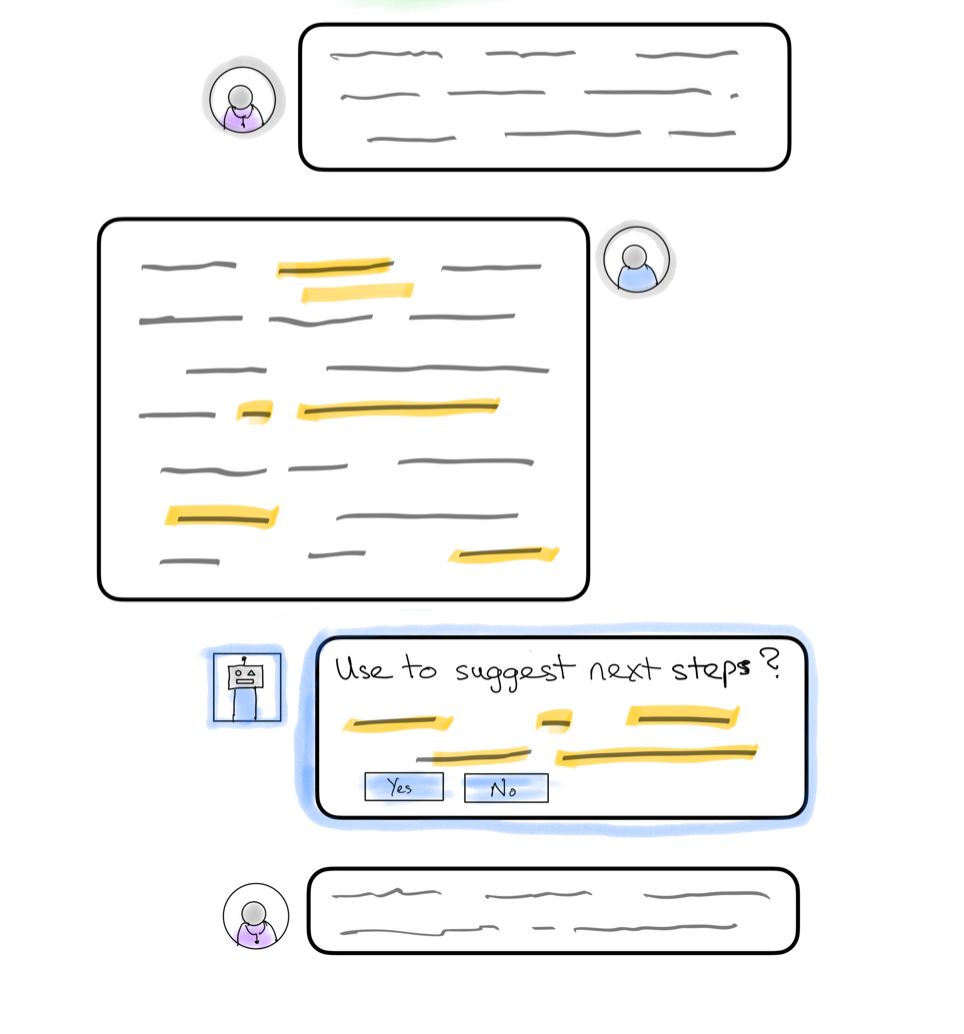

Not all data will be structured because we don't, and never will, live in a world of perfect structured data. AI gives us the chance of spotting data points in unstructured data. For example, during a coaching conversation between a nurse and patient, a service might identify that a patient has shared their weight or symptoms and be asked if they want to use that to update their records. This type of augmented interaction is not, fundamentally, a technology problem - it's a design one. Doing this well, in a way that helps users, builds trust and generates the right outcomes is where the hard work will lay.

When thinking about data in healthcare, it's all too tempting to stop there. AI and interoperability will lead us into the future. But we must not forget that a lot of data points (most?) exist because a clinician has asked for them and a member of the public has reported them.

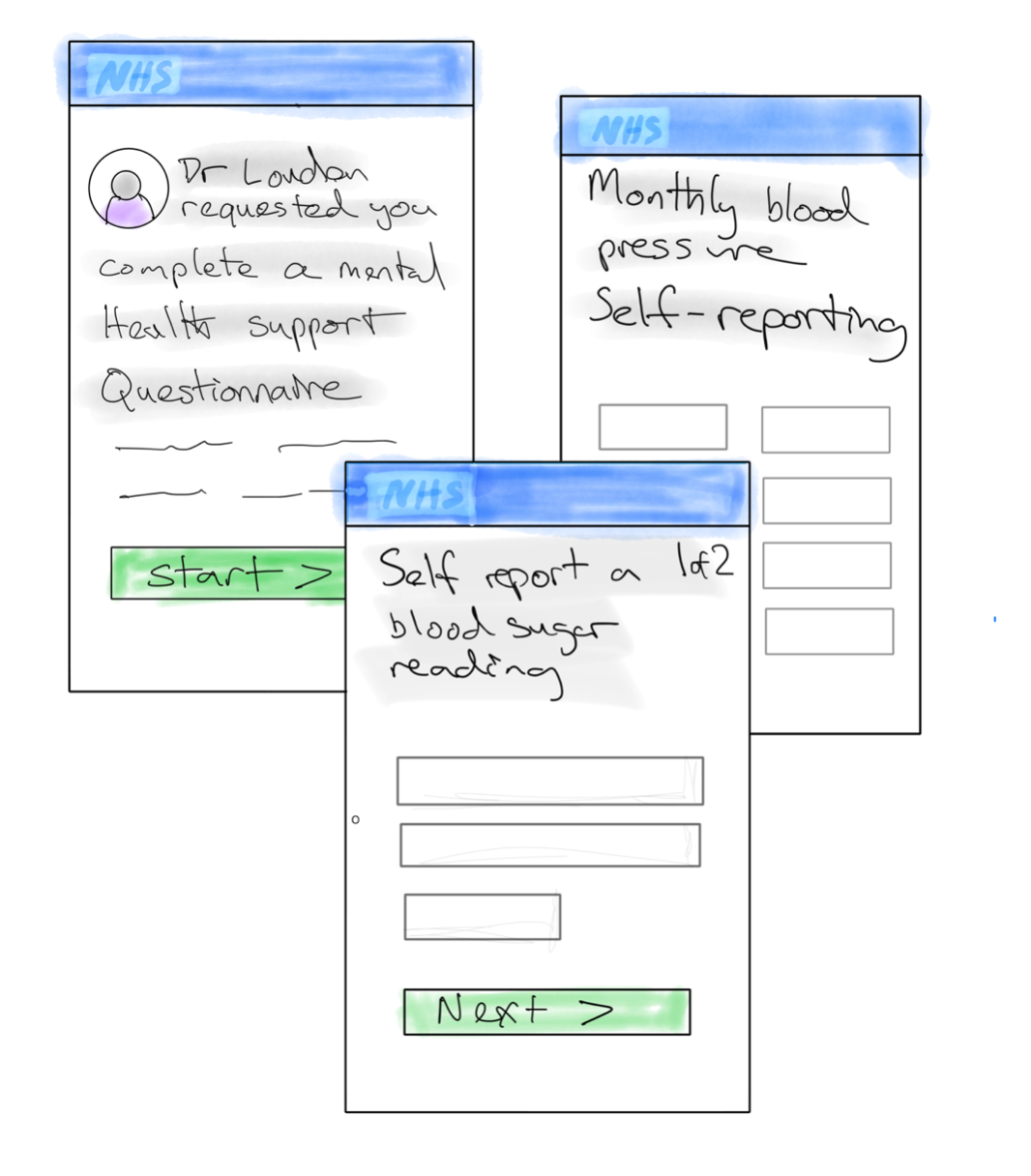

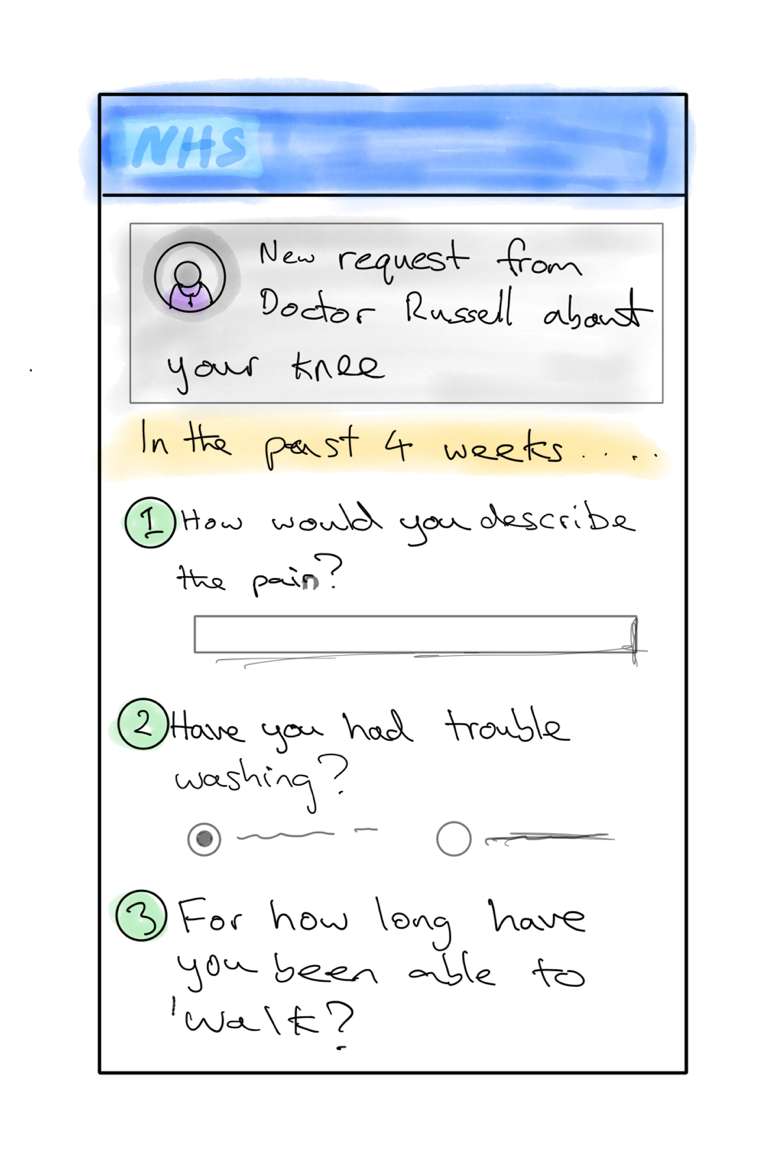

If you search on the NHS domain for 'mental health questionnaire', you'll find dozens of variations on the same forms from different healthcare providers. Some are web forms, many are PDFs or word documents. It's the same for things like blood pressure self-reporting and pain diaries. Every single time has to be attached to an email, printed out, photographed and emailed back, represents unnecessary admin burden for health staff and the public.

Health apps should have the concept of forms as a first-class citizen. Common forms should be designed well and once and linked directly to notifications and reminders. Sending a form should be a single click for a clinician, and completing one should be simple and familiar.

Understanding what it means - create context and connections

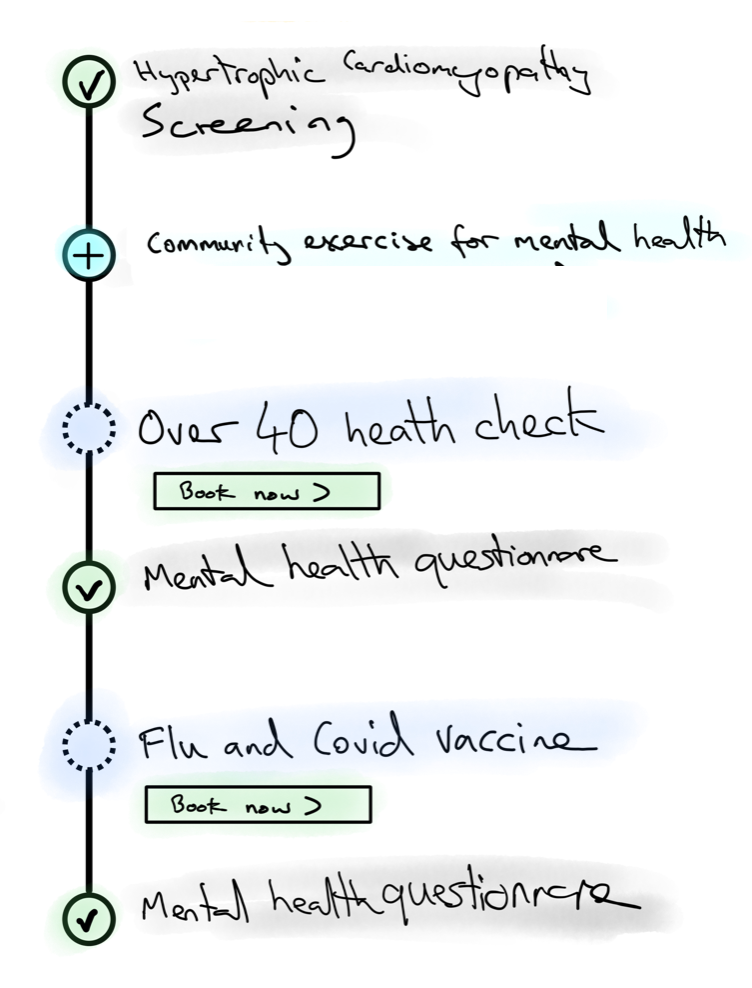

Health records mostly are about the things that happened. Prevention is often about things that didn’t happen - the fact someone didn't attend a health check, or missed a vaccination. Prevention is also often about things that happened outside of a clinical setting - the fact that someone attended a community mental health walk.

A preventative healthcare record could bring all those things together, showing the gaps and celebrating the additional efforts.

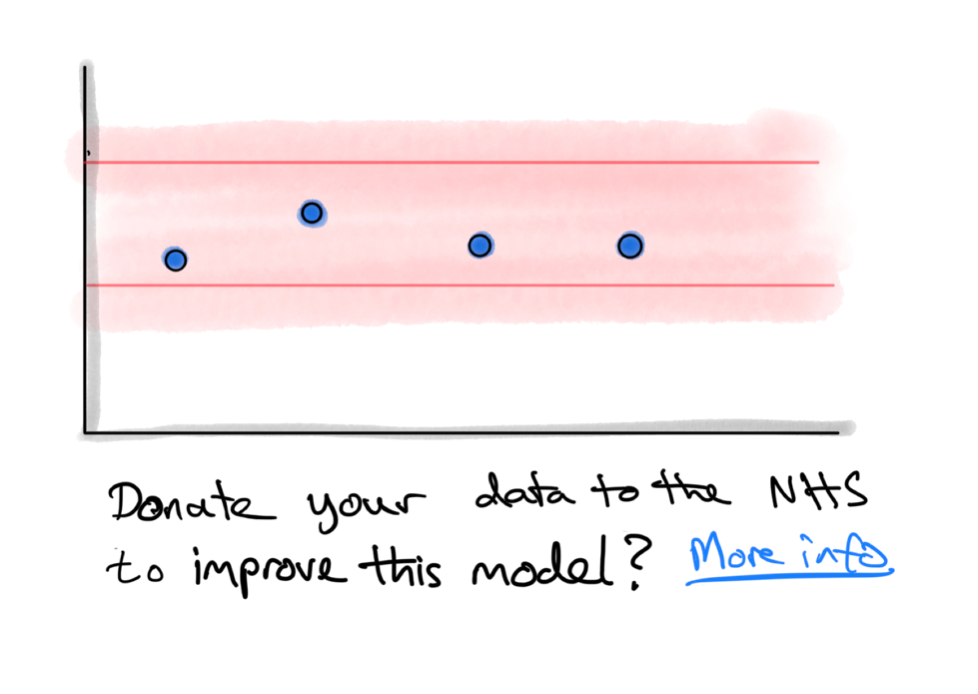

Helping people understand what data means is also about helping people understand how they compare. (If you've not watched it, watch A cool 90’s chart type you might not have seen before by Nat Buckley).

Commercial apps like Apple Health already do something like this, but it could take on a different dimension in the context of a public health system. For example, how about if every time someone's data is displayed alongside community-level datasets, people are also asked to help improve those datasets? Could it start to invert the idea that, to interact with the health system, is to 'burden' that system?

That idea of community is what makes public health systems different. Digital services can build on that by actively building new community connections and a greater sense of ownership.

We can take a cue here from the world of architecture (the built environment type, not the technical type). In Cambridge, there is an award-winning 'co-housing' development called Marmalade Lane. Not only were residents involved in the design, and now manage it together, the design of the development also aims to facilitate community through shared spaces. It's designed to help people bump into each other.

Digital health services should make it simple to ask for help from a broader set of professionals, like pharmacists and neighbourhood health. We could also make it easier to ask family for help in navigating the health system. We might do this, for example, by putting family support (often referred to as 'delegation' in the context of digital identity, but I think that minimises what is going on) at the point of use alongside other triage options.

Understand what to do next - help people look up, help people to act local

There is little use in understanding without being able to know what to do about it. It's like publishing post-code level crime data, but not providing any feedback loops to residents.

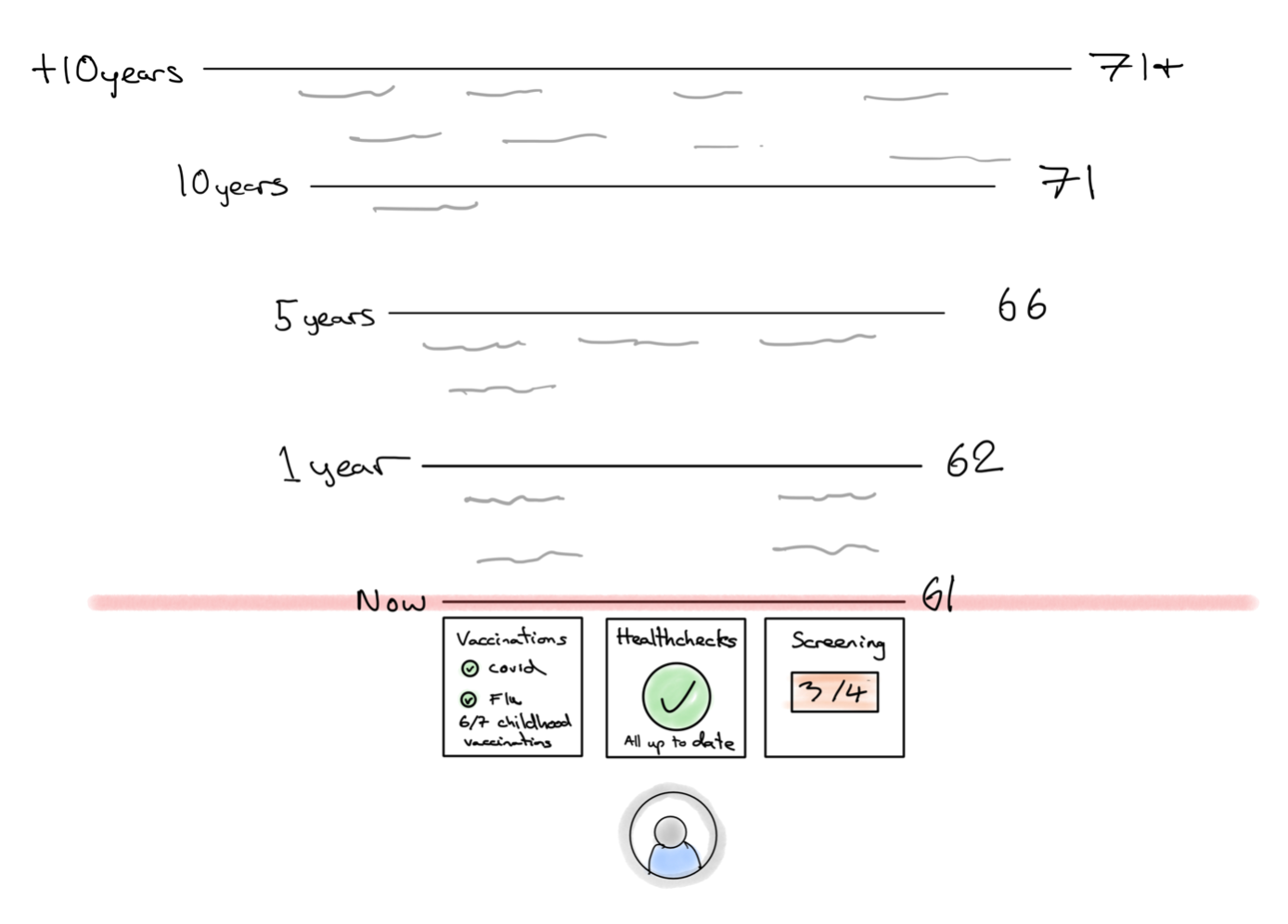

Prevention often about the future - helping people to keep acting in way that helps them stay as healthy as possible. But, as noted above a standard healthcare record is about things that have already happened.

When thinking about a preventative healthcare record, we should imagine something that stretches into the future. Something that represents an opportunity to explain next steps, future screenings, immunity period, medication reviews. That helps people look up from the here and now and think about the future. That future is tricky to design for as its a mix of things that are well known and immediate ("you have a vaccination in 3 months") and the fuzzy (when you are much older, you will likely become eligible for a Covid-19 vaccination").

However, this is another place we can take inspiration from the built environment. Specifically from a map of New York that the design studio BERG created in 2009. Called 'Here & There', it presents a horizonless map of Manhattan where the closest streets and buildings to the viewer are shown in three-dimensions, and those further away curl up into something more like a classic plan view. We should aim to create interfaces like that in healthcare - ones that help people understand what they need to do now, but also help them look up from the immediate day-to-day and plan for the fuzzy future. Designers should see time as a material to be designed with.

Healthcare services are also about place. It sounds almost too obvious to state, but healthcare is something that, more often than not, happens somewhere. In hospitals, pharmacies, doctors' surgeries or the facilities of neighbourhood providers.

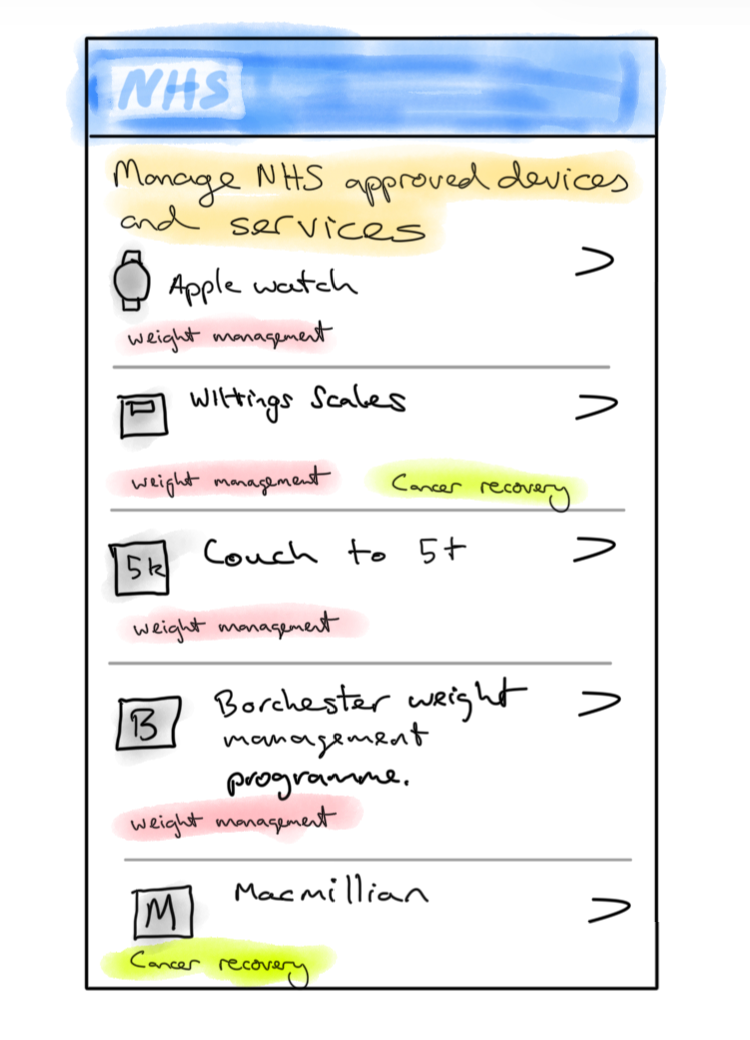

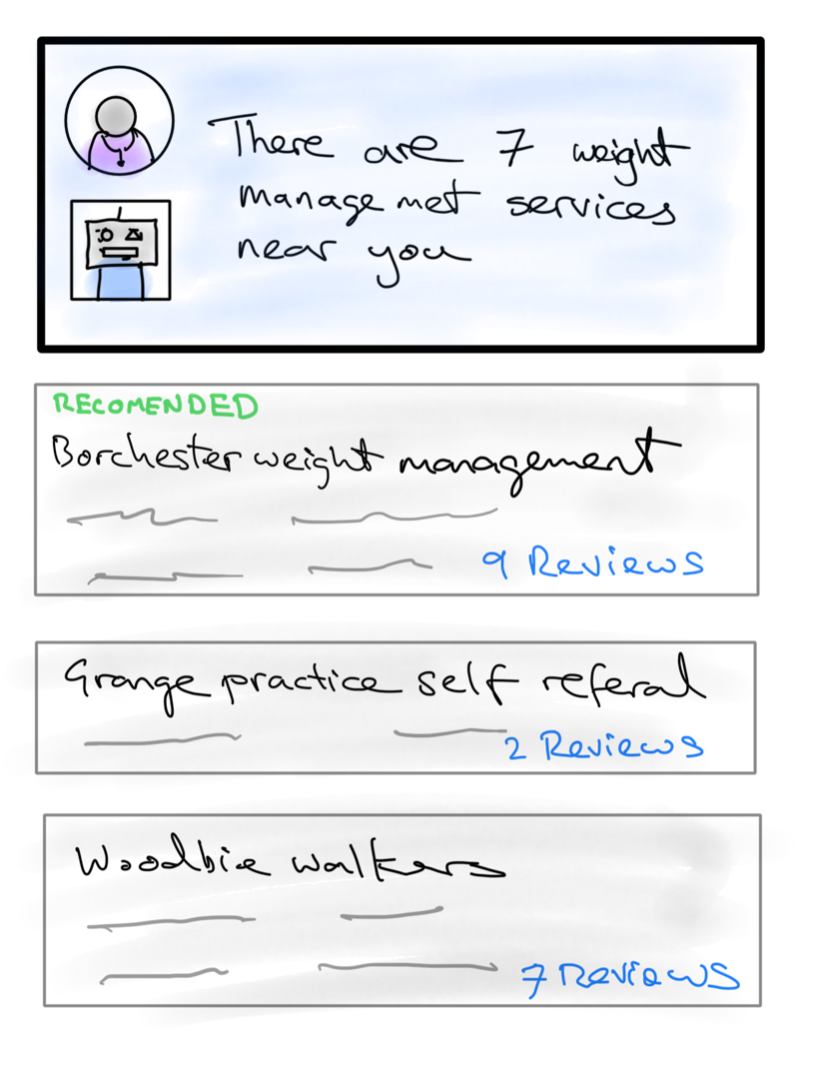

It can feel like there is an inherent contradiction between the desire for more local health delivery and nation state scale apps like England's NHS App or India's ABHA app, but there is not. Products like these bring national scale to local providers, and create predictable, familiar interactions for the public . There provide a surface to curate and access local services.

Without this sort of mindset, there is a risk of replicating the mess of 'local offer' websites that English local authorities must maintain to support children with special educational needs, and that are highly inconsistent in terms of the quality of user experience and are highly bound to local authority boundaries, which often fail to reflect the real geography of people's lives.

Do something - improve flow, don't dictate the route

However, integrating with local services need not just be about signposting. If the aim is to not only refer someone to a local service, but help them to successfully complete the referral too, the national scale of healthcare apps can help here too.

Navigating the healthcare system is more like navigating an airport than it does following a satnav. There is no single route and the variables (late flights, gate changes, weather conditions, crowds) are always changing.

There is an app for frequent fliers called Flighty that is designed around the unpredictability of airports and air travel and I think we should look to for inspiration. Its aim is to help passengers get from A to B with as little stress as possible by using real-time data about flights and airports. It doesn't dictate the path through the airport, it aims to improve the flow of people's journeys through timely updates, reminders and information such as boarding gate information, delays, and notifications about which carousel to collect your bags from on arrival.

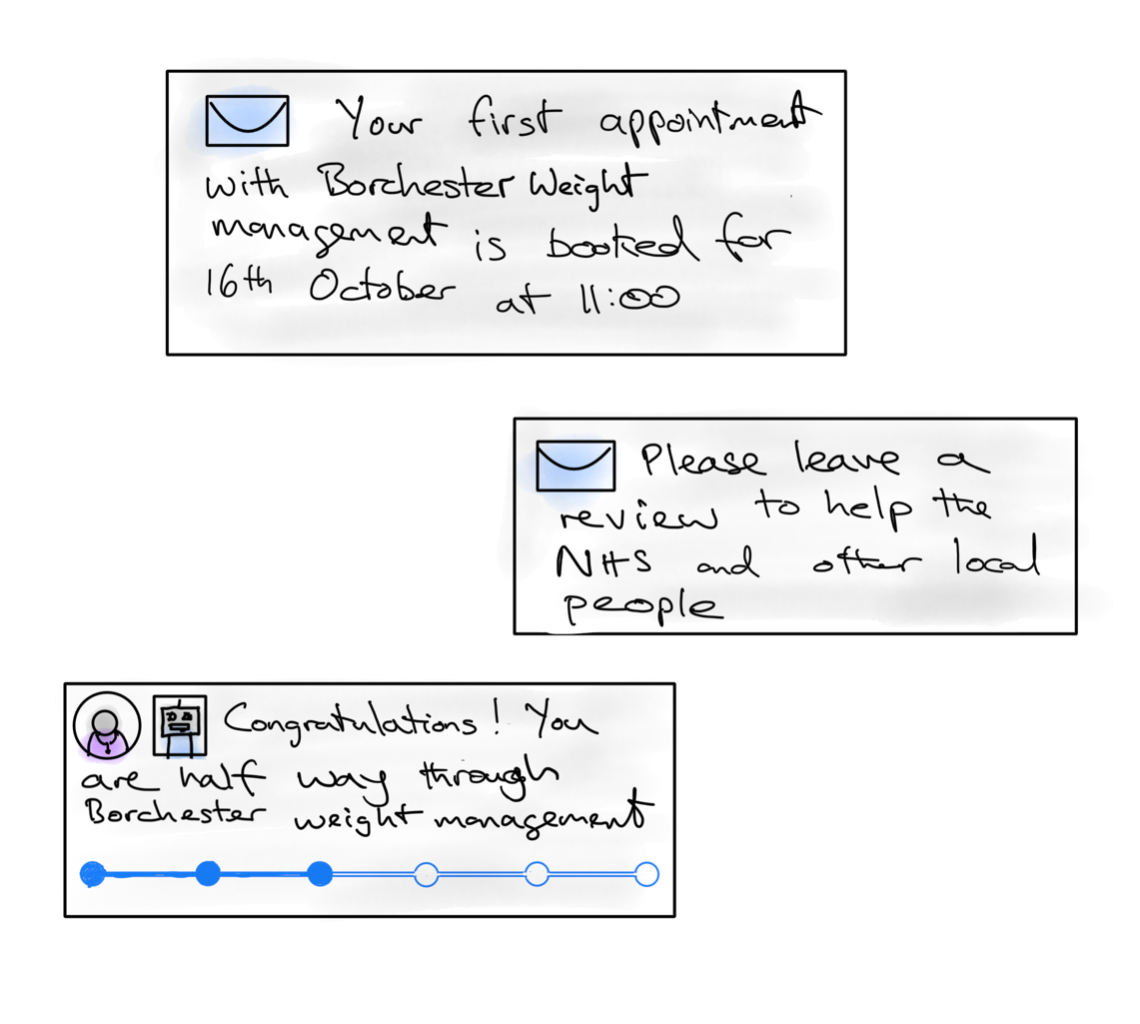

National healthcare apps should allow local prevention services, such as weight management, to integrate more deeply - notifying users of changes to bookings, asking for feedback and encouraging people to complete their referrals.

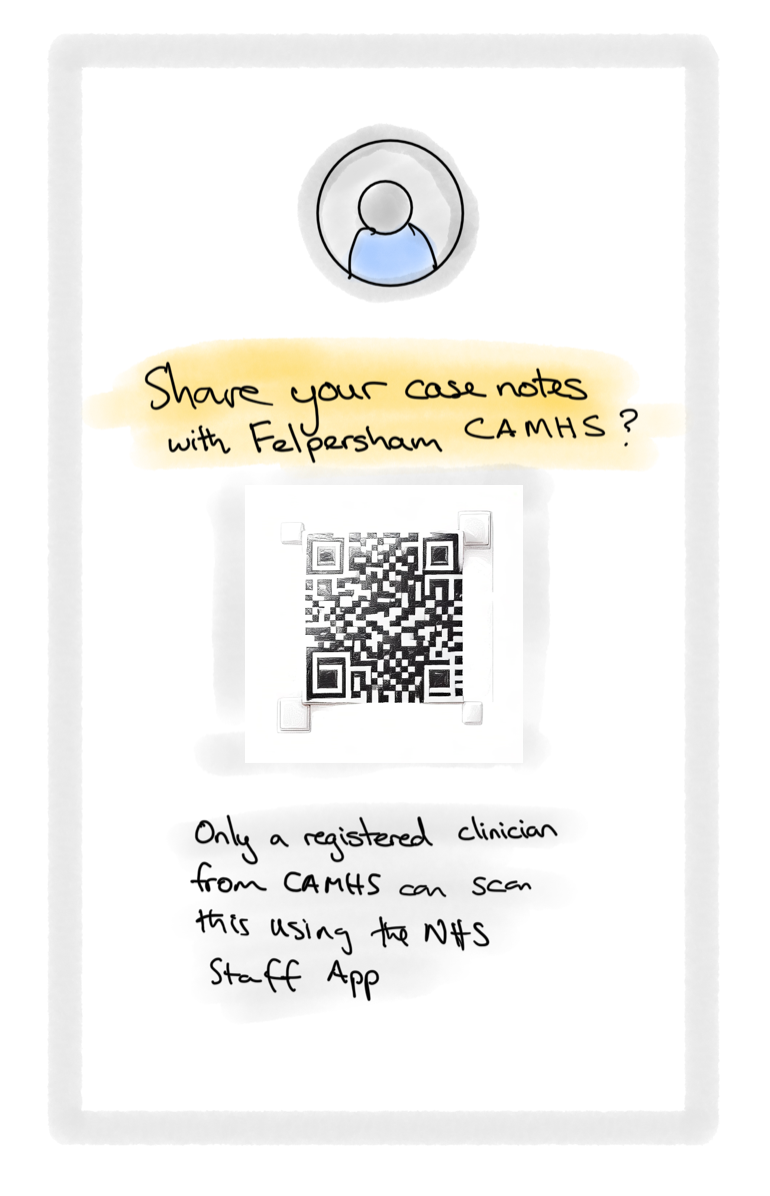

When someone attends a service for the first time, it should help them share data about themselves so they don’t have to retell their story again and again (and make it easier to tell their story if they want to) - just like a boarding pass means passengers don't need to tell everyone at an airport where they are flying to.

More data (again) - close the loop using patient reported outcomes

Every interaction that happens in, or is mediated by a digital service, represents an opportunity to measure that service. It's part of the reason every website is so desperate to get users to agree to cookies. That is something that is well known in the digital profession, but it's mostly absent from health services.

When he was mapping the UK's healthcare sector, researcher Simon Wardley identified patient reported outcome measures (or PROMs as they are known), as a key area for investment. It turns out that there are only a few nationally collected PROMs in the NHS.

Where the NHS does collect PROMs, as with the data collection forms above, it tends to do this with PDFs. This, for example is how the Oxford Knee Pain Score is collected.

The NHS App and other national healthcare services could make the collection of PROMs much simpler by making them a first class citizen in their service offerings to clinicians. What if every booking or notification had the opportunity to attach a relevant PROM questionnaire that would be sent out at the appropriate time?

As Wardley also points out to those who are excited by the idea of AI in healthcare, there is also a clear sequencing problem here:

I do wonder what data these LLMs are trained on given the paucity of PROMs. Maybe rather than billions being poured into AI, it might be an idea to pour billions into PROMs and sharing medical data first.

What needs to be true

Designing for the service loop can never be about designing a single user journey. It is not a single service or a section of app, it's a set of experiences that are sprinkled through a user's interaction with the health system. Those experiences will be different for different people.

Delivering these type of experiences requires product owners who are empowered to look across the range of people's interactions and ensure they remain coherent and aligned with the outcomes the system is trying to achieve. It also requires many teams who are able to work together on something that is greater than the sum of its parts. It's hard to draw parallels with other digital services here. Maybe an operating system like Android are the closest thing?

Also, and most critically, it requires organisations that are set up to experiment. As this blog post hopefully illustrates, there is much that is new in the world of prevention. This lack of prior art has implications for how these services need to be delivered. They are not something you buy off the shelf, and (even more than other public services!) certainly not something that can be specified in procurement contracts. But it's also not something that can be designed or prototyped in isolation. As NHS Product Manager Irina Pencheva puts it:

Behavioural change happens in the messy, unpredictable reality of people’s lives, not in prototypes.

These types of services sit squarely in the category of start small and do it for real. That, in turn, requires institutional leaders to create the structures to enable that to happen. As James Plunkett from Kinship Works points out:

Often, when teams struggle to work iteratively, it is because the operating environment around them is still stuck in pre-2010 industrial structures — most of all because delivery teams are separate from policy teams (or because delivery teams are separate from teams that hold decisions about risk (e.g. assurance or clinical/technical expertise)). This makes it close to impossible to achieve the rapid feedback loops of an agile organisation.

In short, designing preventative healthcare requires health services to organise their people, work and money in a way that allows them to deliver it.